New Zealand’s Productivity Commission has developed draft scenarios to examine the future of work. The scenarios are intended to describe a range of future impacts of technological change on the future of work, the workforce, labour markets, productivity and wellbeing. They will be used to test the effectiveness of different policies.

The Commission is seeking feedback on the scenarios and policy questions.

The first question their issues paper asks is “Are the scenarios developed by the Commission useful for considering the future labour market effects of technological change? “

My initial response is no.

Scenarios are a way of looking at particular uncertainties about the future. Last month I wrote about some UK scenarios about the future of work.

The scenarios

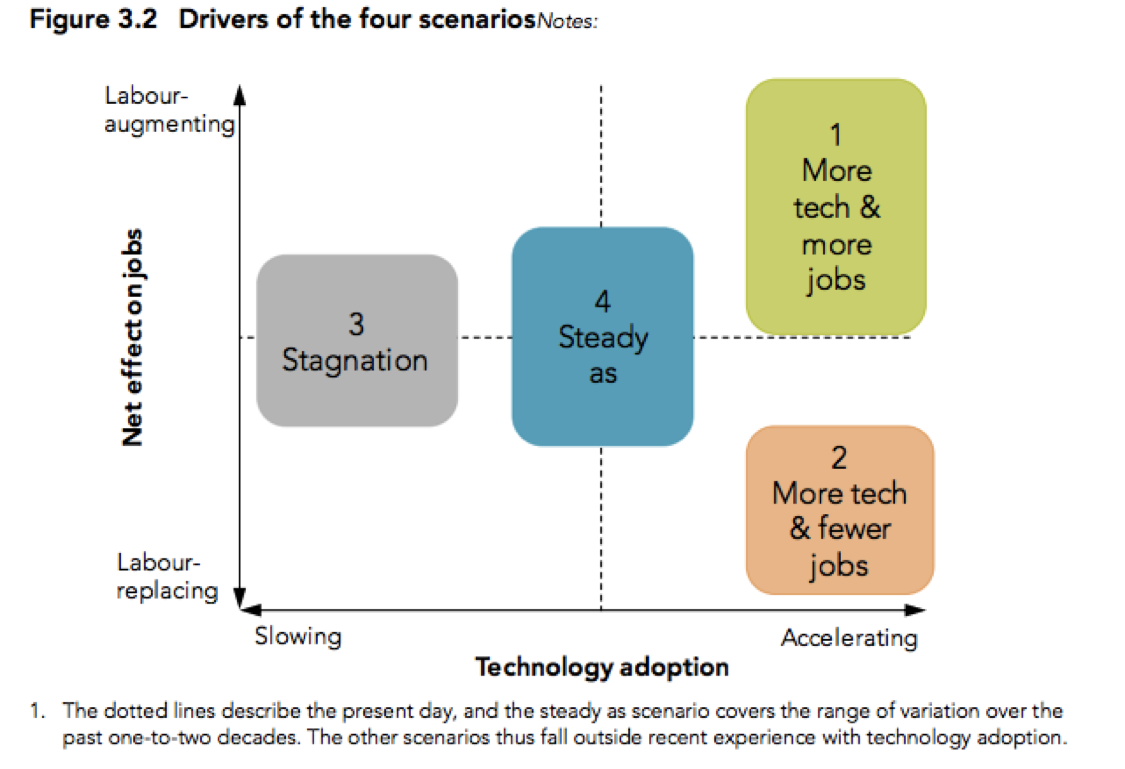

The two key variables that the Productivity Commission look at are:

The rate of technological adoption; and

The extent to which fewer or more jobs are created (or as they phrase it human labour is replaced or augmented)

They don’t describe particular technologies that the scenarios cover, but it’s obvious that the focus is on the emerging suite of technologies associated with computation, automation, and other digital products and services.

The Commission has developed four draft scenarios based on these variables:

Scenario 1: More tech & more jobs

This is where technological adoption is more rapid than at the moment, and that labour is augmented as a result. Firms adopt technologies that improve their productivity, and as a result capital and labour productivity increase.

Scenario 2: More tech & fewer jobs

In this scenario, while technologies are more rapidly adapted, this doesn’t result in more jobs, but with more people being replaced by technologies automation.

Scenario 3: Stagnation

Stagnation results due to a slower pace of technological adoption, which may occur due to a variety of factors. The number of jobs may not change much, but productivity and wage growth are likely to slow or fall.

Scenario 4: Steady as

“Steady as” is the status quo scenario. We adopt technologies over the next few decades at the same pace as recently, with a consequent continuation of slow change in productivity and a relatively stable level of employment.

Source: NZ Productivity Commission

How can the Commission’s scenarios be improved?

The purpose of scenarios is to open up discussions of possible or plausible futures.

I see two main issues with the scenarios at the moment. Both centre on the “possibility space” that they cover. The first is about gaps in their existing frames of reference, the second is about the key drivers themselves.

Possibility spaces

If you accept that the two uncertainties chosen are a good framework (more on this later) the draft scenarios don’t do a good job of covering the possibility spaces. They are biased towards more rapid technology adoption. That may be a reasonable assumption but using scenarios isn’t just about focusing on reasonable assumptions and current experience.

While two of the four scenarios (“Stagnation” and “Steady as”) consider slower or declining rates of technology adoption, there is in their draft form limited difference in the impact on number of jobs. Therefore, the policy value of having them both seems minor.

A possible future not encompassed is where technological adoption slows, or doesn’t change, but more jobs result.

Is this plausible? Yes, look at the growth in craft beers, or high value artisanal honeys and cheeses. Individually each firm won’t employ many people, but if a greater proportion of the workforce was employed in such “artisan” businesses, and these had valuable export deals to discerning markets, that could have a noticeable productivity effect.

Granted, the Commission’s terms of reference are to focus on technological change. But it is useful to include this alternative future since the point is to test policy effectiveness across a range of possible technological futures.

Alternative drivers

All scenarios are simplifications, but if done well they are useful. Good scenarios should provide nuances rather than just simplicities. I think that the two uncertainties (or drivers of change) the Productivity Commission focus on risk being too general to provide a good test of policy options.

The Commission acknowledges other uncertainties in the white paper, but without further refinement attention will be drawn to the numbers of jobs and rate of technological adoption.

In particular, looking broadly at the number of jobs is not very useful. What will be more important is whether there are more “desirable” jobs – in terms of the type of work and their terms and conditions – and that inequalities are reduced, or at least not increased.

A report from the Shift Commission in the US looks at scenarios for the future of work from the workers’ perspective. It notes that US workers seek stability & security of employment over wages and remuneration. This led them to develop scenarios that distinguish tasks (contracts, gigs) from jobs (traditionally structured work).

Incorporating this distinction may be more useful.

I’m also not convinced that a focus on the rate of technology adoption is the most useful driver. Rate of adoption, and diffusion, of productivity-enhancing technologies are important, and can be influenced by policy decisions. But the rate of adoption can be an effect as well as a cause. An adaptable workforce, and capital to invest in new technologies, as well as other factors can determine the rate of adoption.

The RSA’s future of work scenarios (which I wrote about last month) while only four in number looked at different levels of nine variables.

Is four enough?

Giving these complexities I don’t think four scenarios will be sufficient. There is nothing special about having four scenarios, apart from four being easy to remember.

There are four scenario archetypes in the Manoa School of Futures Studies method, but that’s not the approach used by the Commission. They take the management consultancy approach of a 2 x 2 matrix based on two uncertainties. The future isn’t usually that convenient.

The World Economic Forum in a recent future of work white paper looked at three variables, and eight scenarios. The critical uncertainties (with two options for each) they considered were:

Pace of technological change: the pace at which technological change and diffusion occurs

Worker learning evolution: the extent to which workers acquire the right skills to carry out the necessary tasks

Worker mobility: the ability of workers to move within and between countries for work

These provide for a more sophisticated scenario set that recognize the distinction between ability to learn or retrain as newer technologies are introduced, and the fact that the labour pool is global, not insular. The Productivity Commission’s framing risks underplaying workforce regionalism, mobility, and other drivers.

It is important to recognise that the scenarios are not ends. They are a tool to evaluate possible policy options (and business strategy). Having more nuanced scenarios that encompass the range of critical uncertainties are critical for good policy and strategy.

Nonetheless, the Commission’s draft scenarios are an important starting point for discussion and refinement, and it is good to see them seeking feedback on the scenarios before they are finalised. Scenarios are a powerful tool to help influence decision-making. Developing a robust set for New Zealand is essential.